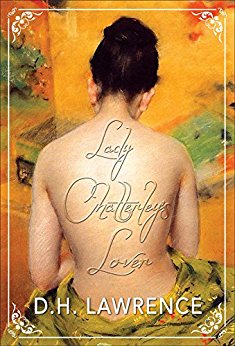

The End of Obscenity: The Trials of Lady Chatterley, Tropic of Cancer & Fanny Hill by the Lawyer Who Defended Them is dear to my heart.

This now-classic received the George Polk Memorial Book of the Year Award in journalism. Random House considered it an important manuscript, and to edit it, I was “loaned out”—assigned to work at the law offices of the author, Harvard-educated Charles Rembar, all day every day for a couple of months. In the conference room, I sat at a big table with him and piles of chapters he’d drafted to stand alone.

The writing was excellent, as Rembar felt a lively rivalry with his first cousin Norman Mailer—not just on the tennis courts. Yet, because of the stand-alone approach to each chapter, he—as he knew—had introduced topics and reintroduced and reintroduced them later on. We were working with a typewriter, not a computer, which meant that I had to turn my brain into a cross-referencing data bank.

So, morning to night (ordering in lunch and taking an evening break for an expense-account-paid dinner at a restaurant nearby), we turned the isolated chapters into a flowing book.

It’s because of Rembar, in part, that I wound up having a private conversation, one on one, with Norman Mailer in a Greenwich Village loft. My friend, mentor, and sometime boyfriend—poet, essayist, and Blake critic Milton Klonsky—had taken me to a party, in the home of actress Geraldine Page and husband Rip Torn. There, Mailer and I discussed his introduction to The End of Obscenity. I had already decided it couldn’t be edited, though I had tried. But it is wisdom to let well enough alone. This was one such situation. Initially attempting to tighten the language, I quickly discovered that Mailer’s style built repetition on repetition; trying to eliminate any of it was like pulling a thread from a carefully woven tapestry.

When I told him that, he commented that maybe he would have liked being edited. My impression of Mailer was of his presence. I felt his full attention and a very responsive face, with energy rippling through it. I was surprised and never forgot. As for Geraldine Page, she would later win an Oscar for Best Actress to massive applause—over Anne Bancroft, Jessica Lange, Meryl Streep, and Whoopi Goldberg; the announcer called her “the best actress in the English language today.” But in this loft party, neither she nor anyone else seemed pretentious. They were artists and authenticity ran deep. Read more on Rembar and the history of banning books in the U.S. in The Guardian.

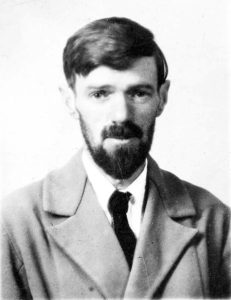

After the successful trial of Grove Press and Rembar, freeing Lady Chatterley’s Lover (D.H. Lawrence), Penguin in England followed suit. Read more on that fascinating prelude to our modern era here in The Telegraph.