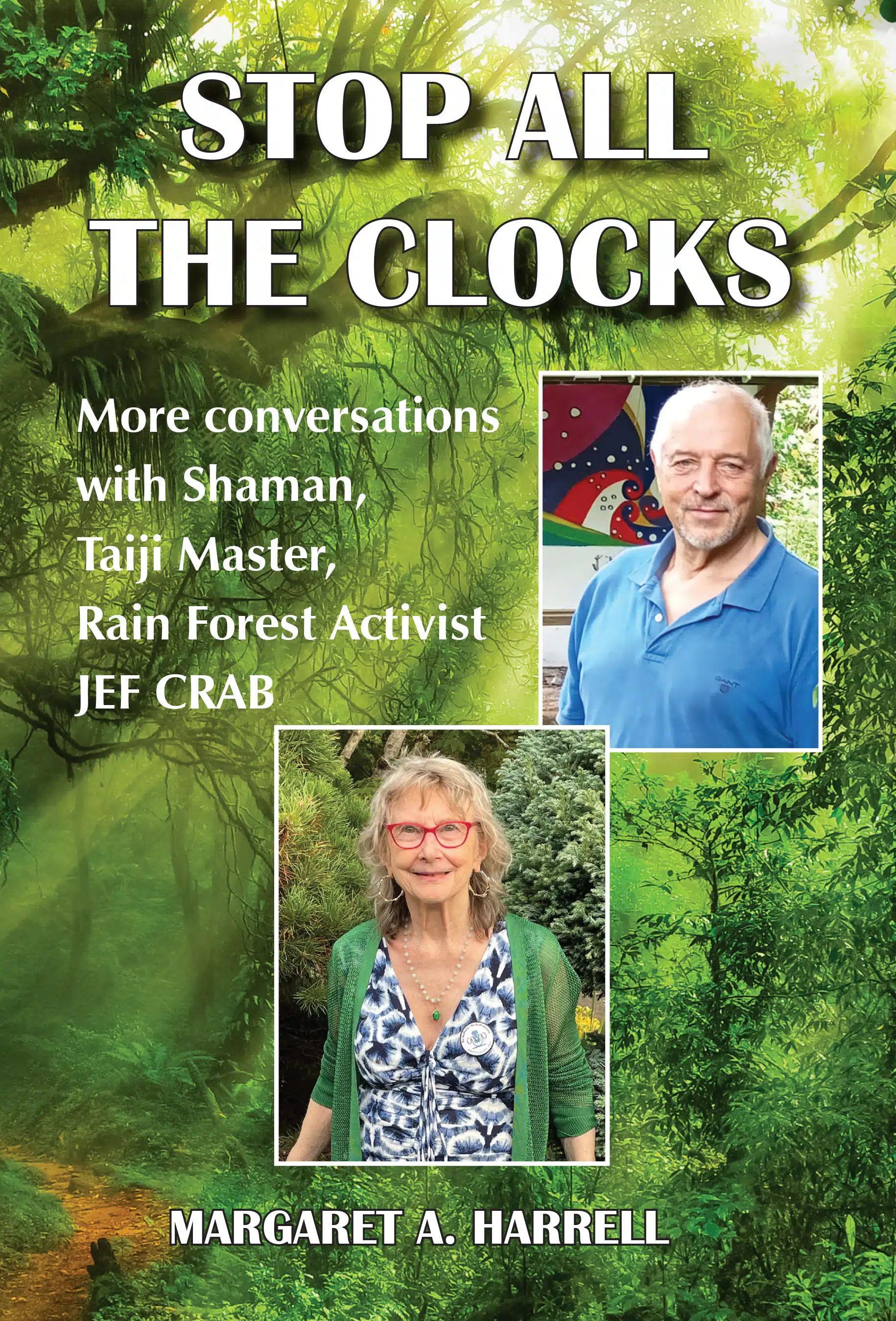

There was a time when books were regularly censored – not just in Communist countries. Right here in the U.S. Living in Greenwich Village, I made a friend of my next-door neighbor, and she in turn used to take trips to Europe in the pay of Maurice Girodias, a publisher notorious for bringing out banned books. Above is an interesting bit of memorabilia from my Greenwich Village days that I turned up just an hour or two ago in my basement archives. The short excerpt below describes some of Maurice’s publications:

In the 1950s, almost everything one wanted to read was published in Paris by Maurice. And banned. Lawrence Durrell, Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, “Pauline Reage &/or Dominique Aury” aka Anne Desclos’ Story of O, Marquis de Sade, Jean Cocteau, Vladimir Nabokov, Chester Himes, Alexander Trocchi, Terry Southern, “Akbar del Piombo” aka Norman Rubington, “Harriet Daimler” aka Iris Owens, Nikos Zorba the Greek Kazantzakis, “Wu Wu Meng” aka Sinclair Beiles’ only novel Houses of Joy, Gregory Corso’s only novel The American Express, Philip O’Connor’s Steiner’s Tour, Raymond Queneau’s Zazie dans Le Metro and Georges Bataille to name just a few. American graduate students earned their tuition by renting out reading copies to undergraduates of the books published by Olympia Press. So when I arrived on the Left Bank during the summer of 1960, having reached the age of my majority, the first thing I did, like so many others of my generation in search of meaning, was head for the bookstalls on the quays along the Seine to buy my Traveller’s Companions, green-covered copies of Henry Miller’s Tropics and William Burroughs’ dust-jacketed The Naked Lunch.

Below in the excerpt from Keep This Quiet! My Relationship with Hunter S. Thompson, Milton Klonsky, and Jan Mensaert, I discuss my interactions with Sarah (who lived in the brownstone next door on Bleecker Street) and, by extension though not in person, Girodias:

Ensconced in my old Village apartment, I was now a Random House copy editor. My own book begun, whomever I met I looked at as a possible character. Bits of many people might figure in.

Next door in another Bleecker Street brownstone was beautiful, thin, elegant, groovy Sarah Uman, the daughter of a black Chicago jazz musician. She was the mistress of Barney Rosset, Grove Press publisher, and would lead me to my main male protagonist. Waging legal wars in the US on behalf of Lady Chatterly’s Lover and Tropic of Cancer, publishing Ginsberg’s “Howl” and Burrough’s Naked Lunch along with Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, to name a few, Rosset, with his Grove Press and Evergreen Review, successfully toppled censorship. In “The Most Dangerous Man in Publishing,” Louisa Thomas wrote, “He found writers who wanted to break new paths, and then he picked up a sledgehammer to help them whale away at the existing order.” More later.

I cultivated Sarah, who occasionally – in tiptop fashion and knockout sophistication – was sent to Paris on business . Rosset told her, she said, “You don’t know how to talk.” He then taught her. Sometimes I babysat her son. I believed he was Rosset’s, though perhaps he wasn’t. For my book I confiscated his line: “What’s a mecent mixer?”

I have to admit that babysitting was a ploy. I hoped through this association to get back with Lawrence . Once again I found myself in a room with a bowl of pot, which she said to help myself to and I didn’t. One night Sarah invited me to have a drink at the Corner Bistro. She stopped across the street at 375, to pick up the eccentric Marguerite Young—almost fifty, newly famous for Miss MacIntosh, My Darling—whose apartment I remember for the angels hanging from the ceiling. Young had received a Guggenheim and taught at Columbia, the New School, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Walking three abreast— Marguerite Young with short, straight, unglamorous hair, in a long dress with shawls and scarves—we headed out. Marguerite had spent nearly eighteen years on her thousand-plus-page novel. I was to beat that record, though I had no idea of such a prospect. Under other circumstances, this chapter would recall my unforgettable evening with Young. But that was wiped from memory by what happened next .

Click here for the NYT obituary of Girodias: A very colorful life, with many literature classics published by his press – Lolita (1955, Vladimir Nabokov) and The Ginger Man (1955, J. P. Donleavy), for example – which, at the time, battled charges that they were pornographic.